If Chinese had a Valentine’s Day, it would be the Qixi Festival. Based on the legend between the Weaver Goddess and the cowhered––mythology of forbidden love, like that of Hades and Persephone––Qixi Festival provides an opportunity for young unwed women to gather together, worship the Weaver Goddess of love, and compete for dexterity. Qixi is unmistakably rooted in patriarchy: through the holiday, men could judge women’s ability to care for the house, subvert her to the role of homemaker, and value her only for her assets. Modern for a holiday yet traditional in its intention, Qixi is not only one of the earliest love festivals in the world, but a representation for the longing of women during this historical time period.

One of these arbitrary yet highly-implicit competitions engages women in needle-floating contests. This test of dexterity supposedly rules out daftness in the female entrants. This year, and approximately 4 centuries later, I decided to parttake on this contest to extrapolate my homemaker capabilities. Boys, listen up.

The Floating Needle Contest

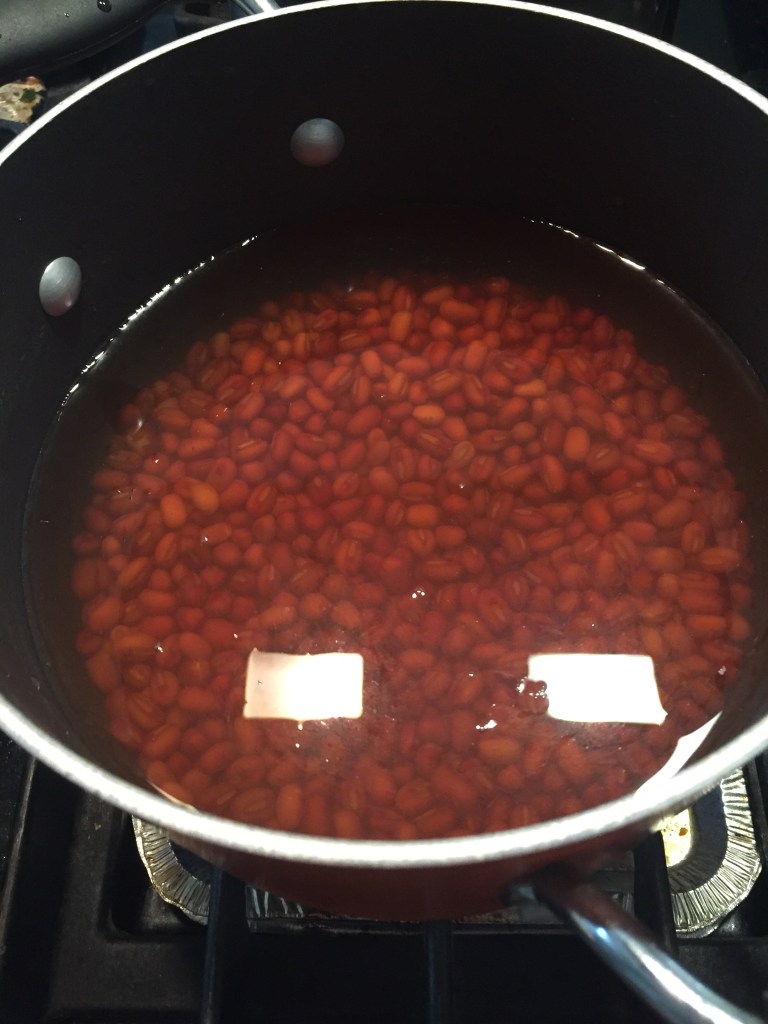

The floating needle contest prevailed during the Ming and Qing Dynasties as a traditional Qixi custom, first recorded in Beijing Geographic 帝京景物略. The day before Qixi, young maidens concocted Yuan Yang water 鸳鸯水, a mix of water from different sources. They either poured half river water and half well water into a washbasin, or took halves from the same sources once in the morning and once at night. The water sat outdoors overnight and bathed under the sun the next morning. At noon of Qixi, awaiting hands tested their dexterity by taking turns to place an embroidery needle on the surface of Yuan Yang water. If the needle floated on top of the water, the woman flaunted a steady hand; if the needle sank, she was out of the game, and maybe even out of the waiting list of potential wives. But she shouldn’t lose her hope so soon: the needle created a shadow at the bottom of the washbasin that uncannily foreshadowed one’s future. If the shadow formed a pattern of clouds, flowers, birds, animals, or even elaborate objects such as a pair of shoes or scissors, she won prosperity and the blessing of happy marriage. Unfortunately, a simple straight line, whether thick as a club or thin as a string of silk, demonstrated insufficient dexterity to bring a promising future. Looks like I’m going to have to find my own means of socio economic self-efficiency.

At noon, I carried out bowls and several of my grandmother’s antique needles onto the patio floor. In order for the needle to cast a shadow in the water, the sun must directly shine over the bowl.

Balancing the needle on the water was more difficult than I expected. I’m uncertain if women were given the leeway to “cheat” a bit by using paper support underneath; ensuring that all the water molecules densify to create an elastic membrane for buoyancy is unattainable. So I caved and used paper, which was supposed to disintegrate and eventually fall into the water.

But even regular paper proved unworkable. I’m really not housewife material. I had to sneak 2-ply toilet paper out into the yard. Fortunately, toilet paper disintegrated while allowing the needle to remain on the surface of the water.

The shape of the shadow came out quite like amoebas or thick rods, despite multiple tries. I question how shadows forming into Nike Airforce 1s, Gucci handbags, clouds, tulips, and birds is biologically possible. Or maybe I’m just a sour loser for cheating and then losing the game.

This 21st-century pursuit of a 16th-century ritual served as an opportunity to reflect upon ancient patriarchal ideals and the draconian contests through which Chinese women could prove their worthiness. So meanwhile holidays demonstrate what’s celebrated by cultures, it also shows what isn’t. I think there’s some power to that.